The woes of the labourers’ working conditions is one of the most frequent themes tackled in these songs : the inhumane nature of the work and the fear of unemployment are the most recurring themes, as well as alcoholism and the pawnshops. The news are also discussed: going to or coming back from war, the important public figures visiting the city, and comments about the government’s policy.

Two song leaflets, one is written in Lille patois (Les consolations du café, Lille, imp. Alcan-Levy [missing date]) the other one in Roubaix patois (Pontier L., Feuilles de chanson Les misère de France, [missing place], imp. Leveugle, [missing date]). ©Gallica

Desrousseaux Alexandre, Le Mont de Piété (Chansons et Pasquilles lilloises, édition de 1938, HR12 0330)

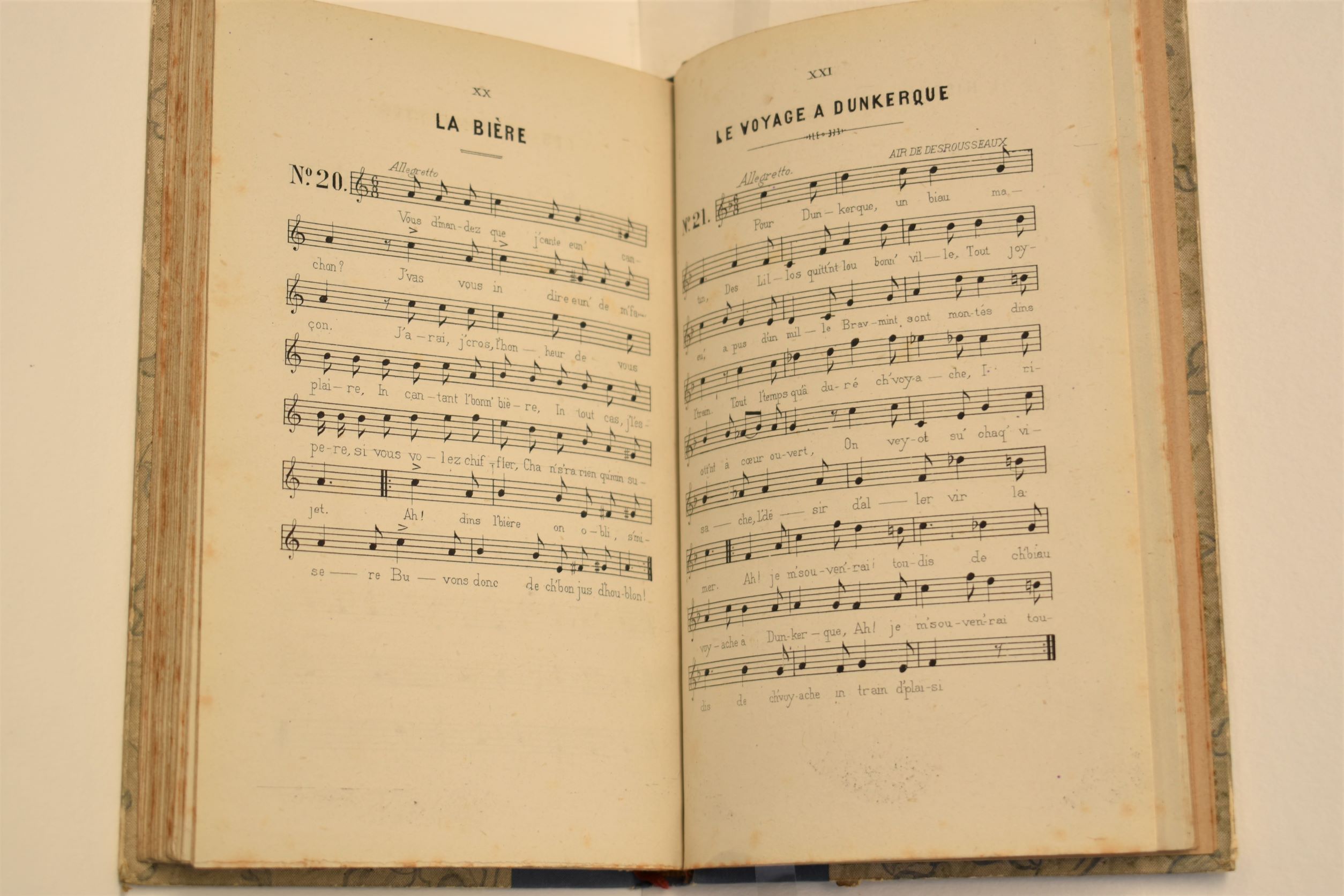

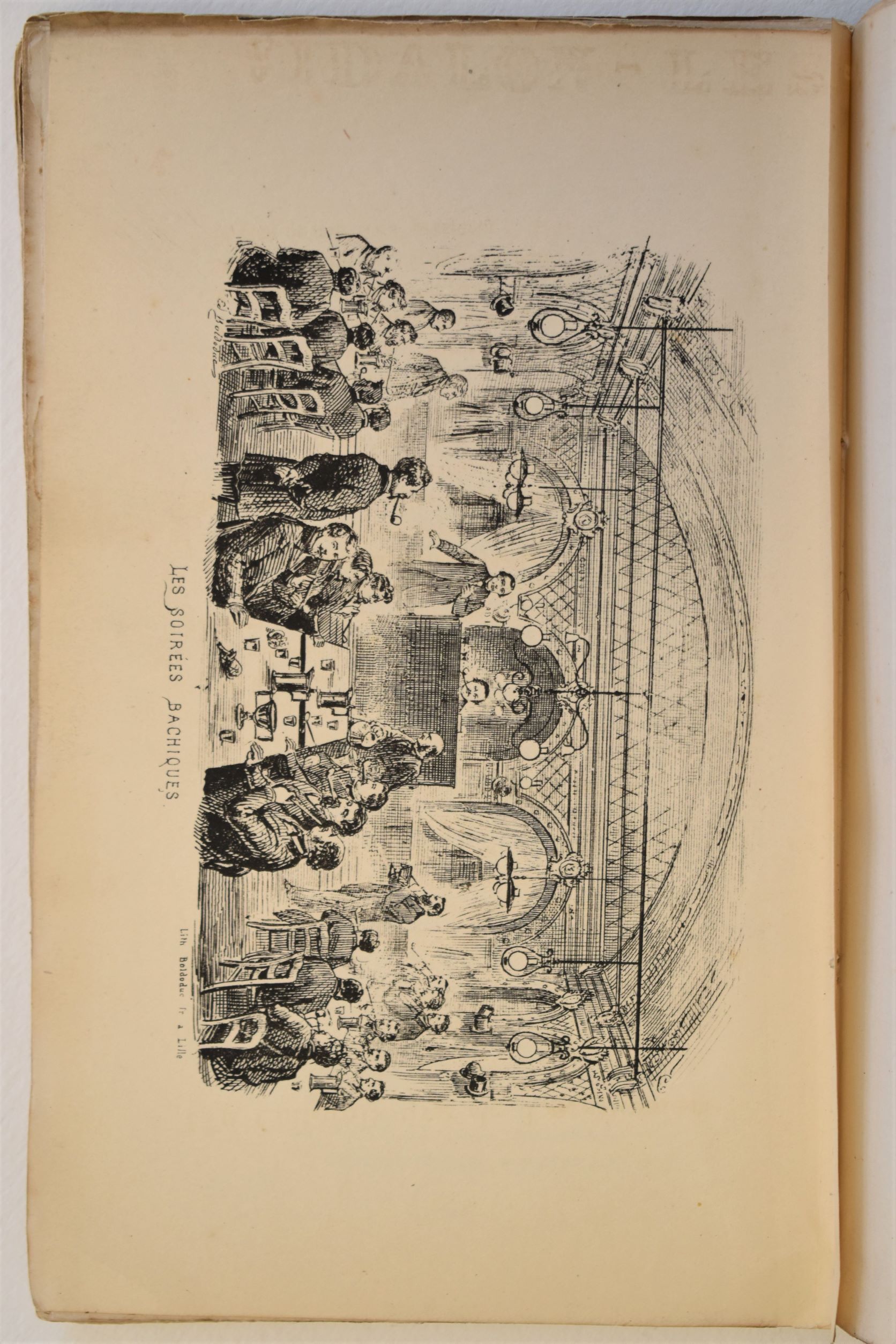

However the most common themes are celebrations such as Carnival or Mid-Lent, or other festive events : weddings, fairs, and town events ; of course, the societies’ nights out singing and drinking also appear quite often in those songs.

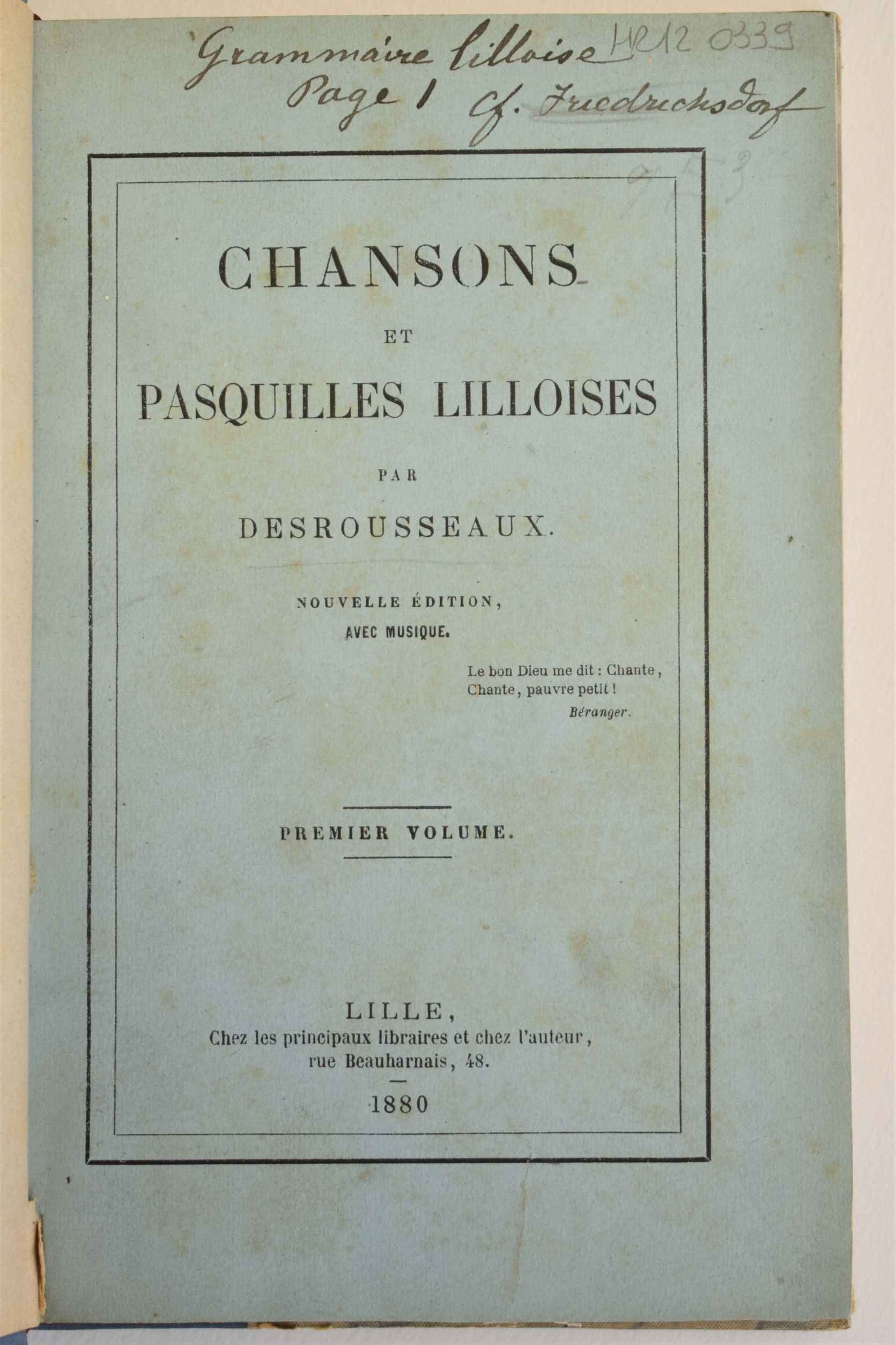

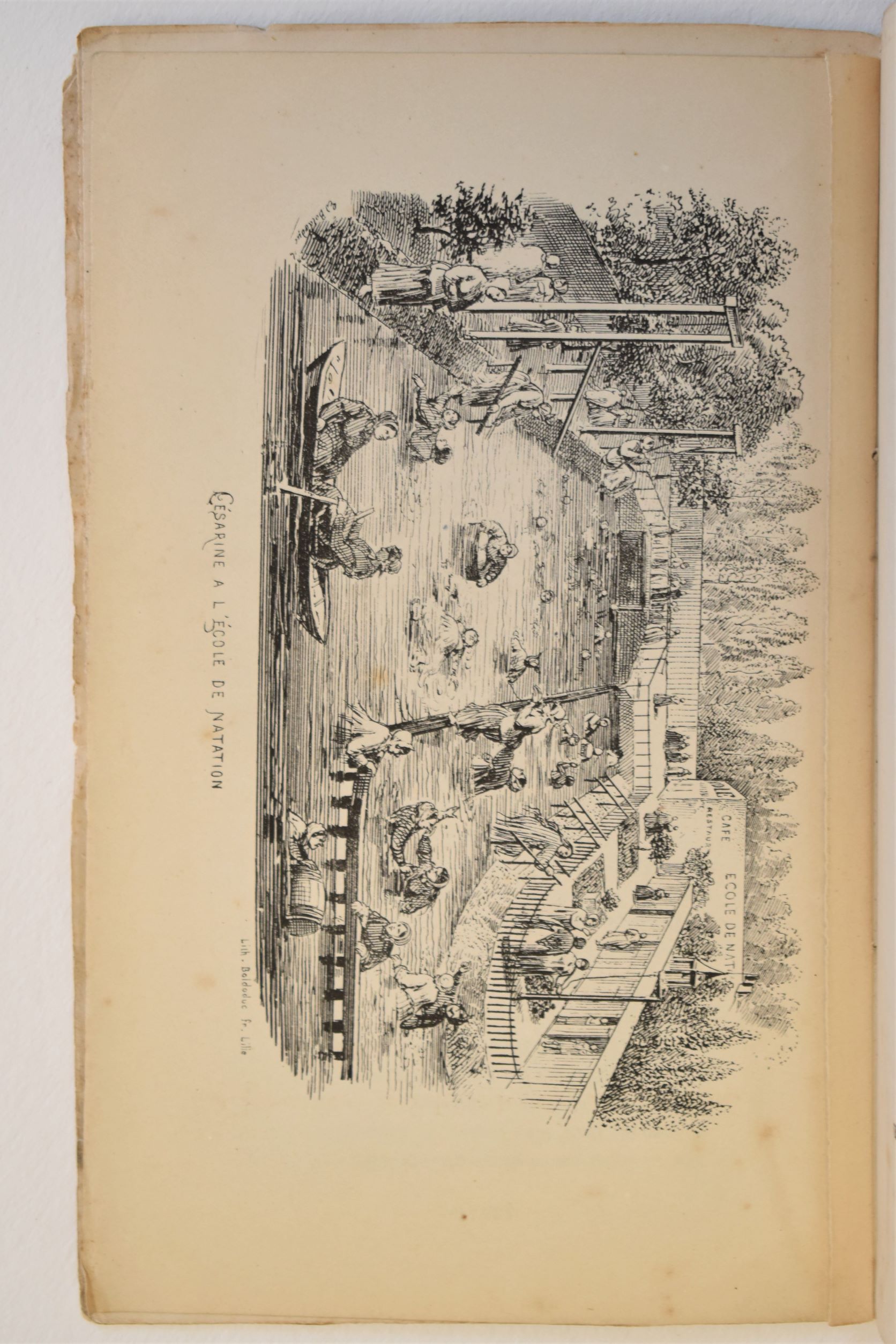

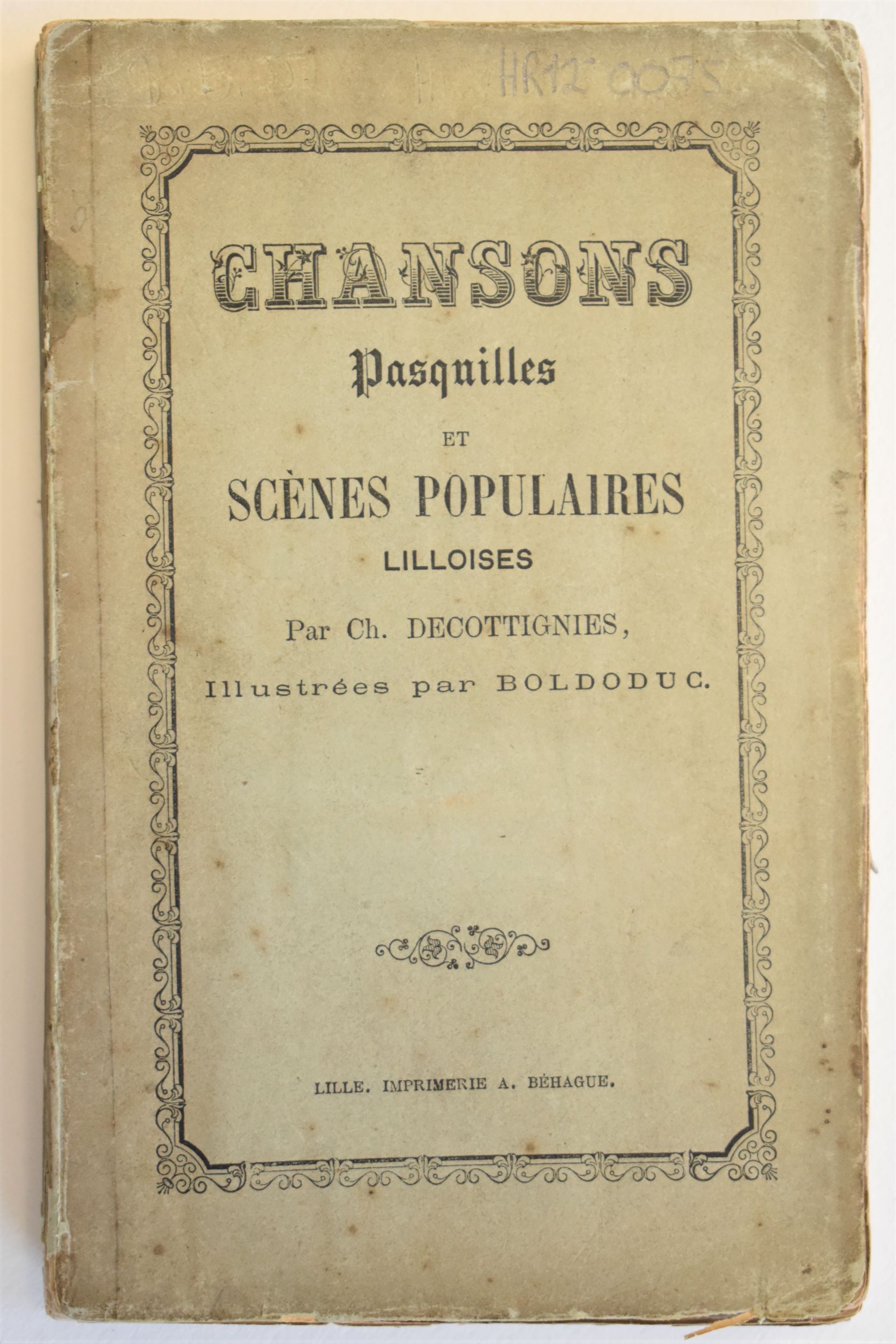

Desrousseaux, “La Bière et Dunkerque” (Chansons et pasquilles lilloises, Principaux libraires edition, 1880, HR12 0339). Decottignies, “École de natation et Soirées bachiques” (Chansons, Pasquilles et Scènes populaires lilloise, 1864, HR12 0075).

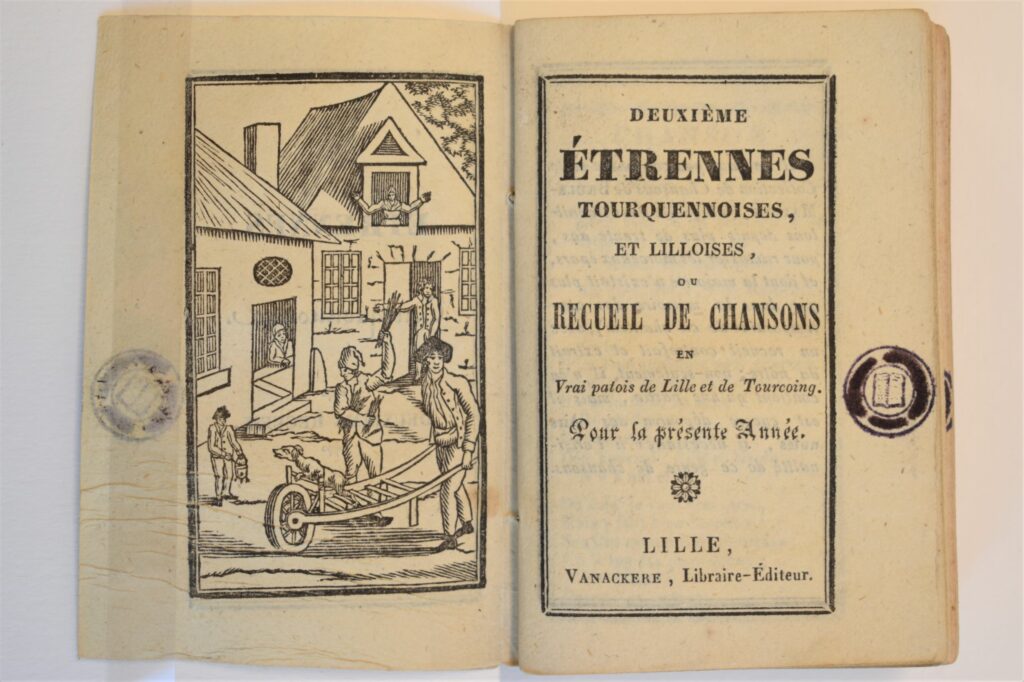

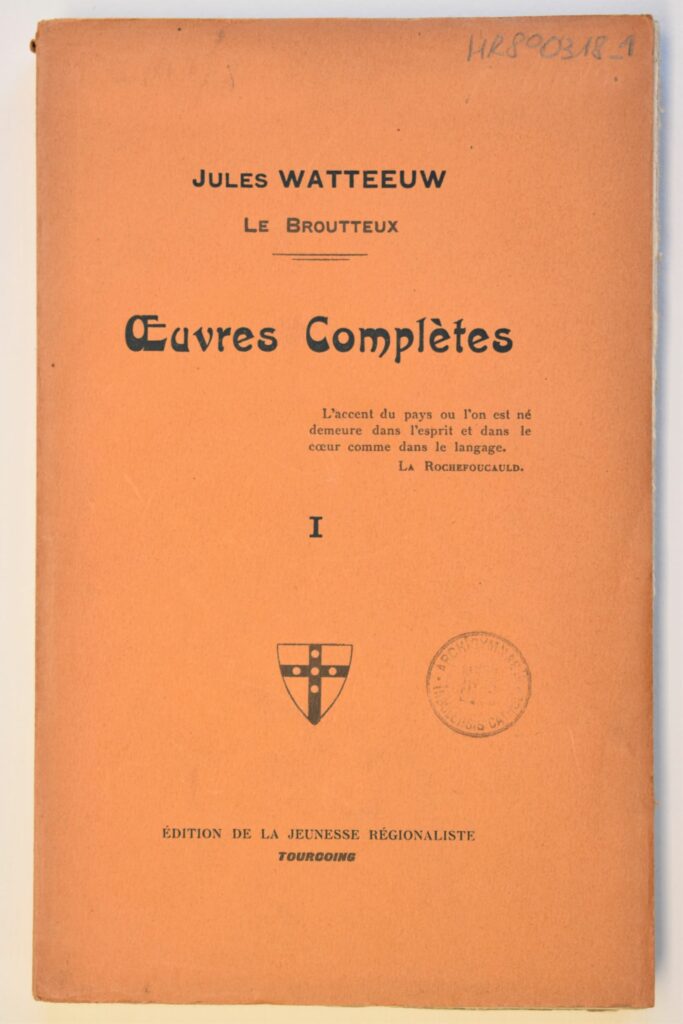

Farcical fantasies, like the ones written by Brûle Maison from Lille. In some of those he makes fun of the “broutteux” from Tourcoing, people who would bring their meager produce to the Lille farmers’ market. In order to come to Lille, they would push their wheelbarrow over the 10 miles separating both cities, hence the nickname “broutteux”. On the next century, Jules Watteuw embraces his Tourcoing origins and takes the name “Broutteux” to write his songs.