Before the beginning of the 19th century, written music was mostly for religious celebrations, and most of the written songs were religious chants.

Collection of songs and verses on many topics, 18th century manuscript. 1M25. Notice the lack of music sheet, since the only indications about the melody are “to the tune of…”

Street singers already existed, but the lyrics of their songs as well as their language, the patois, fly off like the “Carnival sheets” on which they are printed. Those song sheets were sold for a few cents each in cabarets or on the street and only during the festivities. Indeed, the writers took the risk of being subject to fines, which means very few documents – and in poor condition – have been preserved.

Page of “Chanson de Carnaval” on a famous 1851 tune that has now disappeared. ©Gallica.

Song sheet for “L’impôt sur les capiaux”, played by the society of the Amis Réunis. ©Gallica

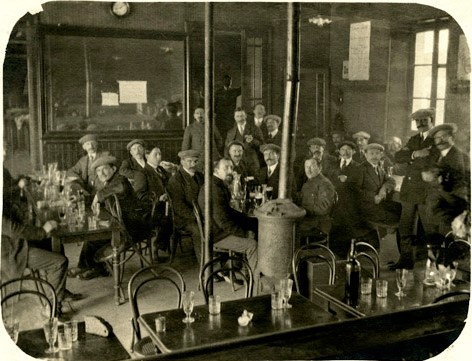

Popular songs will have to wait until the beginning of the industrial revolution and the Second French Empire and the expansion of estaminets, cabarets and “societies” of singers to find their longevity in the written form. In 1874, Lille counted 1500 of those. In Tourcoing, there was one for every 50 inhabitants.

Courbet G., sticker for a word on the Andler-Keller brewery, in Delvau A. Histoire anecdotique des cafés et cabarets de Paris, E. Dentu, Paris, 1862 ©Gallica

Agence Rol, “23-11-13, Lens, grèves du Nord [une rue d’un coron], 1913 ©Gallica

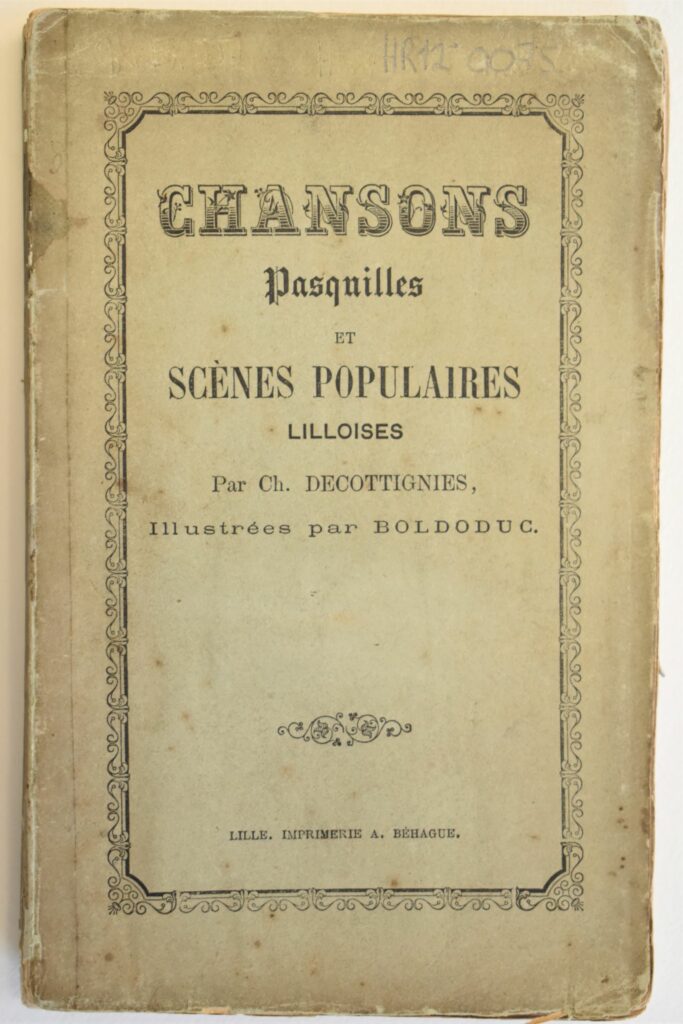

The publication of leaflets and song collections allowed the working-class chti patois, a mostly oral language, to endure and thrive on paper.

Petite notice sur l’orthographe du patois de Lille, call number HR12 0330-1

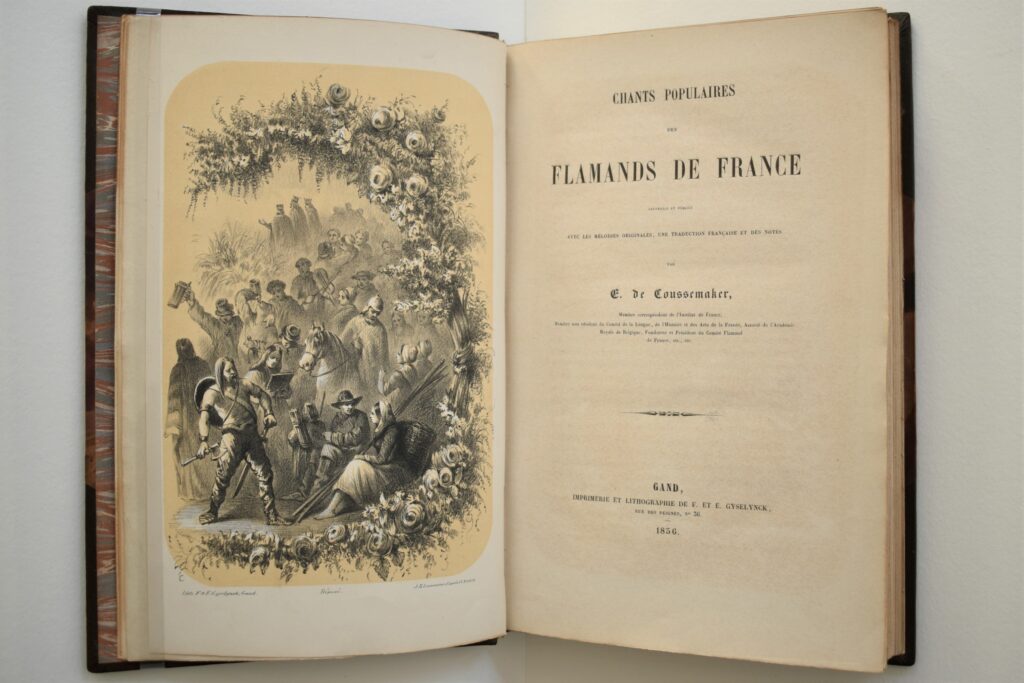

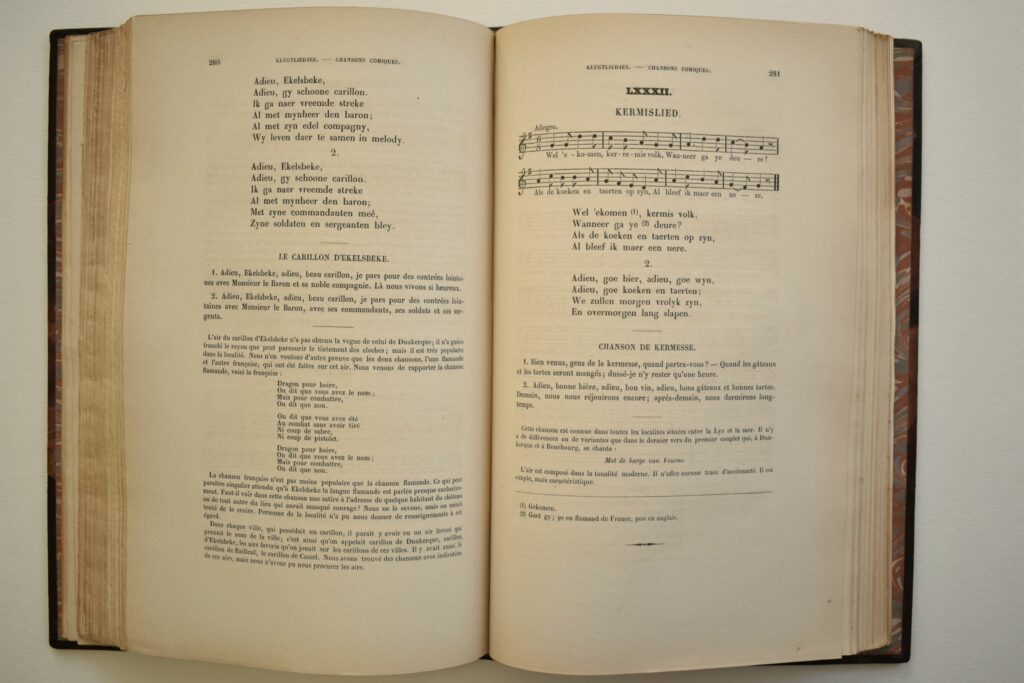

The first editions of these songs lead to the realisation of that heritage. In 1856, Edmond de Coussemaker published Chants populaires des Flamands de France, which gathers texts written in French and Flemish, as well as religious and secular songs. Those songs were annotated with captions that explained the text, in order to pass down the heritage.